|

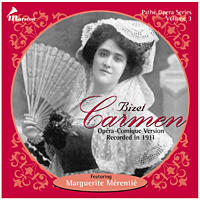

Carmen Opéra-Comique Version - Recorded in 1911 - Featuring Marguerite MérentiéBizet's Carmen, the first of eleven complete operas recorded by the Pathé Company, is reissued here for the first time. An important historical document displaying the unique French style of singing, this 2-CD set is the first complete recording of Carmen in French and the only recording with spoken dialogue before 1950. Opéra-Comique's musical director François Ruhlman (1858-1948) leads Marguerite Mérentié (1880-?) as Carmen, alongside legendary opera stars Agustarello Affre (1858-1931) and Henri Albers (1866-1925) who perform brilliantly as Don José and Escamillo. Aline Vallandri (1878-1952) presents a beautifully lyric Micaëla. |

|

|

Liner Notes

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

Carmen

Opéra-Comique Version Recorded in 1911

Featuring Marguerite Mérentié

Opera in four acts

Recorded in fifty-four parts

Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy

Based on the novel by Prosper Mérimée

| Don José | Agustarello Affre |

| Escamillo | Henri Albers |

| Le Dancaïre | Hippolyte Belhomme |

| Le Remendado | Paul Dumontier |

| Zuniga | Pierre Dupré |

| Moralès | Mr Dulac |

| Carmen | Marguerite Mérentié |

| Micaëla | Aline Vallandri |

| Frasquita | Marie Gantéri |

| Mercédès | Jeanne Billa-Azéma |

François Ruhlmann, conductor

OPÉRA-COMIQUE, chorus and orchestra

THE PATHÉ OPERA SERIES

The French Pathé Company undertook the prodigious task of recording a series of eleven complete operas and two complete plays in French, which was collectively entitled “Le théätre chez soi” (Your Theater at Home). The enterprise began in 1911 and by the end of 1913 nine operas and two plays were on disc. In 1922 and 1923 two additional operas were added to complete the collection. Although the Pathé opera project turned out to be a commercial failure, it is impossible to overestimate the historic and musical significance of the Pathé series. These recordings transport us back to an era when the lost art of French singing still flourished in Paris.

Listening to any of the operas in this series gives one the palpable impression of an actual live performance although the sound on the original discs is primitive. This is in large part due to a rudimentary recording method which Pathé employed. Each master recording was originally made on a large wax cylinder. The next step in the process involved playing the cylinder back and transferring the sound to a wax disc which became the master for the issued record. This was accomplished by means of an acoustical connection between the diaphragm of the cylinder reproducer and the diaphragm of the disc recorder, much like two tin cans at either end of a taut piece of string. All Pathé discs are, therefore, one generation removed from the original master, and consequently, the sonic quality of each disc hinged upon exactly how well the cylinder-to-disc transfer was made. Unfortunately, Pathé seemed to have no concept of quality control, and their issued discs ranged from surprisingly vivid to dreadfully anemic. Not surprisingly, transferring the original discs to the digital domain presents a great challenge. Every effort has been made to keep the pitch constant, to join the sides according to the score and to provide the best quality possible.

Ward Marston

The image of Carmen--hand on hip, flower in mouth, head tossed back defiantly--is etched in our visual memory as indelibly as portraits of the Madonna or Mona Lisa. With a look that mingles indifference and menacing allure, she seems to say, "Love me if you can, but you will never possess me." Photographs of Marguerite Mérentié show a statuesque but beguiling gypsy with kohl-drenched eyes about to toss her cassia flower at José or, fan in hand, attired in her finery, calmly awaiting their final encounter. At once inviting but unattainable, cool and threatening, Mérentié conveys the enigmatic look of the classic Carmen.

Few operatic heroines are more alluring--to the women who sing her as well as the men who pursue her. The first Carmen, Célestine Galli-Marié, was a light mezzo-soprano. Subsequent interpreters have come in every vocal form, from heroic sopranos like Lilli Lehmann and Emmy Destinn to deep contraltos like Ernestine Schumann-Heink and Jean Madeira. Carmen has attracted singers as disparate as Adelina Patti, a famed Rosina, and Martha Modl, a mezzo turned soprano who sang Lady Macbeth and Brünnhilde.

Few female singers have withstood the spell cast by this irresistible character. What other operatic role allows an artist such limitless interpretative possibilities? In Carmen's first entrance, a singer must find the smoky, languid tone appropriate for the Habanera but she must also project, in both look and movement, predatory menace as well as teasing sexuality. Carmen sings sultry arias and dramatic duets. She seduces men and abandons them. She fights, dances, plays castanets and smokes cigarettes. She lives freely and dies fearlessly.

Carmen can be approached from many dramatic angles, most contradictory. She, after all, is called both "sorcière" and "gentille," "démon" and "mignonne." A singer can play Carmen as a tigress or a tabby, slut or lady, femme fatale or coquette. Maria Gay and Ninon Vallin represent the two interpretative poles. Gay, a Spanish mezzo with a booming voice, played Carmen as a coarse, vulgar gypsy. Boldly impudent, she shocked critics with "her kicking, spitting and nose-blowing." Following Mérimée if not Bizet, she chewed an orange and spat out the seeds before singing the Habanera. Vallin, on the other hand, was not interested in being either coarse or common. The elegant French soprano made a cool, intimate, somewhat straight-laced cigarette girl. When Tyrone Guthrie staged Bizet's opera at Sadler's Wells, he turned Anna Pollak into what one English critic called a "vulgar, violent slut." When Gladys Swarthout brought her glamorous Carmen to the Metropolitan Opera, she astonished audiences with her sleek costumes and careful coiffure. "Too much the perfect lady," complained one New York critic.

Vulgar slut or elegant lady, Carmen can also be played as a heroic woman or playful lover, a demonic sex goddess or teasing flirt. Lilli Lehmann, famed for Wagner and Mozart, made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1885 not as Isolde but as Carmen. W. J. Henderson later recalled that Lehmann "astonished operagoers by presenting a Carmen of heroic mold, sinister and tragic, but with none of the subtle sensuality associated with the character... " A century later when Teresa Berganza introduced her portrayal at the Edinburgh Festival, she surprised audiences with the lightness and intimacy of her characterization. Here was a mercurial Mediterranean woman, light of voice, quick and agile of movement, far removed from the Germanic grandeur of a Lilli Lehmann.

It would, perhaps, be easier to list the singers who have not sung Carmen than to catalogue those who have. Few have resisted the temptation to bring this fascinating character to life. Leontyne Price, Maria Callas and Anna Moffo left complete recordings, but none dared to undertake the part on the stage, aware, perhaps, of other singers' failure. Patti succumbed to the temptation but suffered a setback surpassed only by Nellie Melba's disastrous attempt to sing Brünnhilde. "Carmen may have been a cat," scoffed Henderson, "but Patti made her a kitten." Even Herman Klein, the soprano's partisan biographer, was forced to dismiss her portrayal as "clever but colorless." Patti, noted Klein, lacked the low range to sing the role and ornamented the vocal line with pointless embellishments. The soprano later denied she ever sang Carmen.

J.B. Steane has called Carmen "one of those roles in which it is difficult to make little impression." Carmen is also a role that invites excess. When Maria Jeritza brought her gypsy to the Met in 1928, she created controversy. One critic reproached her for singing the fourth act like a "screaming, scrapping fishwife" and compared her second-act dance to "a genuine Coney Island hoochy-cooch." Henderson gave a more detailed critique. "Mme. Jeritza was very busy," he reported. "She made a vigorous attempt at a Spanish dance; she sprawled on tables and chairs, put her feet in men's laps, jumped on tables and off again and smoked cigarettes even while singing... But with all her energy she did not seem to get far beneath the surface of the role."

Rosa Ponselle suffered a shocking setback when she undertook Carmen at the Met. Ponselle coached the role with Albert Carré and wore costumes designed by Valentino. Despite her meticulous preparation, Ponselle's conception was rejected by the critics. In The New York Times, Olin Downes belittled her acting and complained of her "bad vocal style, carelessness of execution, inaccurate intonation." Rounding out his critical catalogue, Downes added, "Her dancing need not be dwelt upon, although in the Inn Scene it raised the question whether Spanish gypsies preferred the Charleston or the Black Bottom as models for their evolutions." The reviews were so devastating they shattered the soprano's confidence and contributed to her withdrawal from the opera stage a season later.

Carmen has been described as "a baffling part" as well as "a dream role" and at least one famous interpreter, Risë Stevens, has called the role "a killer." Even so, she remains irresistible. Galli-Marié had already created Mignon by the time she appeared in Carmen. Her unique talents were acknowledged at her debut in La Serva Padrona at the Opéra-Comique in 1862. A critic described Galli-Marié in words that show her suitability for Bizet's gypsy. "She is small and graceful, moves like a cat, has an impish, pert face, and her whole personality seems unruly and mischievous. She acts as though she had been trained in the sound tradition of Molière. She sings in a full, fresh voice, piquant and mellow."

The most celebrated Carmen of the nineteenth century was not Galli-Marié but Minnie Hauk. The American soprano first appeared in Carmen in Brussels in 1877 and then sang the role more than 500 times in English, German and Italian as well as in French. Hauk introduced the opera to both London and New York. Her vivid portrayal was recalled by Klein. "The gypsy appeared strutting forward with hand on hip and flower in mouth... The voice itself was not remarkable for sweetness or sympathetic charm, though strong and full enough in the middle register, but somehow, its rather thin, penetrating timbre sounded just right in a character whose music called for the expression of heartless sensuality, caprice, cruelty and fantastic defiance."

Hauk became so identified with Carmen that French newspapers claimed she was Spanish, not American, and reported that, before turning to opera, she had been a female bull fighter. Other important Carmens in this era were the Viennese-born Pauline Lucca and two more Americans, Clara Kellogg and Zélie de Lussan. A critic called Lucca "a very tigress with cruel claws ready to dart forth and rend and tear on the slightest provocation. The slightest brush the wrong way turns our fascinating gypsy into a fiend."

Geraldine Farrar triumphed as Carmen both at the Metropolitan Opera and in Hollywood, where she starred in a silent film version directed by Cecil B. DeMille. When Farrar introduced her portrayal in New York in 1914, Henderson reported, "She was indeed a vision of loveliness, never aristocratic, yet never vulgar, a seductive, languorous, passionate Carmen of the romantic gypsy blood."

A year later, Farrar returned from Hollywood with new stage business that scandalized some of the Metropolitan Opera's staid patrons. The soprano engaged in a rough fight with chorus girls and even slapped Enrico Caruso. Farrar later denied all that. "Fantastic stories were spread abroad that I assaulted chorus girls in the opera, due to malignant violence prescribed in the movie," she wrote. "That I chewed the ears of timid supers and slapped King Enrico such a resounding smack that the audience gasped as it caused him to falter in his song and sputter maledictions. All pretty reading perhaps, but none of these charming inventions occurred."

The most famous of all Carmens was French soprano Emma Calvé, supreme as both singer and actress. In her memoirs, Calvé claimed to have been the first Carmen to introduce authentic gypsy dancing into the opera. H.E. Krehbiehl called her first New York Carmen "the most sensational triumph ever achieved by any opera or singer." "That she is the greatest Carmen ever to trod the stage is indisputable," added Henderson. "Her dramatic temperament is overwhelming and her means of expression is beautiful and eloquent." Klein agreed that her Carmen was incomparable. "It had the calm, easy assurance, the calculated dominating power of Galli-Marié's; it had the strong sensual suggestion and defiant resolution of Minnie Hauk's; it had the panther-like quality, the grace, the fatalism, the dangerous impudent coquetry of Pauline Lucca's; it had the spark and vim, the Spanish insouciance and piquance of Zélie de Lussan's... The wonder of the melange added to exquisite singing made Calvé's assumption from first to last superlative."

Calvé's Carmen is documented in countless photographs and numerous recordings. Why didn't Victor seize the opportunity to record her in the complete opera? Although Suzanne Brohly, Lucienne Bréval, Genevieve Vix and Marthe Chenal sang Carmen at the Opéra-Comique, Pathé chose Mérentié (1880-?) to portray the gypsy in the first complete French recording in 1911. Within a year of graduating with First Prize from the Conservatoire National, Mérentié made her debut at the Paris Opéra on 15 May 1905 as Chimène and in the next three years sang Valentine, Sieglinde, Elisabeth and Aida. She returned to the Palais Garnier in 1913 to sing Isolde and Brünnhilde in Die Walküre. These roles and the dark coloring of her voice suggest Mérentié was a soprano dramatique. In 1909, she joined the Opéra-Comique, making her debut as Carmen with Edmond Clément as José. Mérentié had already sung Carmen in a gala performance that introduced Bizet's opera to the Palais Garnier two years before. At the Comique, she sang Ariane, Fanny, Tosca and Charlotte. Mérentié made guest engagements at Monte Carlo, the Théâtre de la Monnaie and La Scala where she created the title role in Xavier Leroux's Theodora. Other creations included the title part in Massenet's Ariane, Saint-Saens' Ancêtre and André Gailhard's Le Sortilège. After giving up her career for marriage in 1919, Mérentié slipped into obscurity. In addition to Carmen, she recorded Nouguès' Les Frères Danilo for Pathé, three sides for G & T in 1907 and fourteen single sides for Pathé between 1911 and 1913.

Like Mérentié, Aline Vallandri (1878-1952) studied at the Paris Conservatoire. She made her debut at the Opéra-Comique in 1904 as Mireille and sang a wide swath of the lyric soprano repertory, from Manon, Micaëla, Louise, Mélisande and Pamina to Violetta, Donna Elvira, Tosca and Rosenn in Le Roi D'Ys. At the Salle Favart, she created roles in Chérubin, Le Roi Aveugle and La Légende du point Argentan. Guest engagements took her to Monte Carlo, Brussels, Lisbon, London, Cologne and Zurich. For Pathé, she sang Gilda in the complete recording of Rigoletto.

Mérentié and Vallandri--by reputation, at least--belong in the second class of French singing artists. In contrast, Agustarello Affre and Henri Albers rank among the elite. Affre (1858-1931) held his own with Escalaïs, de Reszke, Van Dyck, Alvarez, Saléza, Scaremberg, Muratore and Franz in a career that lasted two decades. After studying in Toulouse and at the Conservatoire National, Affre made his debut at the Paris Opéra in 1890 as Edgardo in Lucia with Nellie Melba. He soon claimed leading parts in Les Huguenots, Guillaume Tell, Aida, Faust, Samson, Sigurd, L'Africaine and Roméo et Juliette. At the Opéra, he created roles in operas by Massenet and Saint-Saëns and also sang Canio and Belmonte for the first time. Affre never sang at the Opéra-Comique, but during his career he made guest appearances in Lyon, Marseille, Brussels, London, New Orleans, Havana and San Francisco. A prolific recording artist, he recorded a lengthy repertoire for Zonophone, G & T, Columbia, Pathé, Fonotopia and Odéon.

Albers (1866-1925) centered his career in Paris but enjoyed international success. Born in Amsterdam, he pursued a theatrical career until his voice was discovered. After making his debut as Méphistophélès in 1889, he sang in Antwerp, Le Havre, Bordeaux, Monte Carlo and London. During the 1898-99 season, he undertook a wide range of roles at the Metropolitan Opera but was not re-engaged. Before returning to France, he appeared in San Francisco, New Orleans and Havana. His Paris career began in 1899 at the Opéra-Comique, which was to remain his artistic home until his death. At the Salle Favart, Albers sang in Lakmé, Carmen, Mireille, Louise, Pelléas, Tosca, Werther and others. He created roles in Bloch's Macbeth and Moret's Lorenzaccio and enjoyed a major career as a guest artist that took him to Berlin, Leipzig, Vienna, Milan, Monte Carlo and Zurich. In one season at the Paris Opéra, he sang in Tannhäuser, Thaïs and Thérèse. Albers recorded frequently for G & T, Odéon and Pathé. He is featured in complete recordings of Rigoletto and Roméo et Juliette as well as Carmen.

Led by Opéra-Comique's music director, Fran�ois Ruhlmann (1858-1948), these singers capture the flavor of a performance at the Salle Favart less than forty years after the premiere of Bizet's opera. Recording conditions in 1911 were far from ideal. One wonders how much rehearsal and how many takes the singers enjoyed. The Pathé Carmen was recorded long before Walter Legge envisioned the ideal cast giving the ideal performance or John Culshaw imagined a sonic stage for his opera recordings. Despite the limitations, this Carmen is an important historical document--the first complete recording and the only recording with spoken dialogue before 1950.

By 1911, Affre had already sung his best performances. Aside from trouble with the high climaxes, he rises with assurance to the demands of José's music. Vallandri brings a shining spinto sound to Micaëla--her voice soars in the ensemble ending act three. Albers impresses with the elan and vigor of his singing. Encompassing the extremes of the range, his firm voice blares out confidently in the Toreador's Song. And what of Mérentié? She may well be the discovery of this historical set. Her voice, dark but not weighty, focused and pliant, ranges seamlessly from a full but unbosomy lower range to a shining top that never glares or loses its focus. She sings with polish and an innate feel for the drama. Marston hopes to document the work of this neglected singer with the reissue of her complete solo recordings. The Pathé Carmen whets a collector's appetite for that release.

© Robert Baxter, 1999